Unitary maps promise fewer layers and better value, but change is bumpier than the pitch. In three quick case studies, I have a brief look that the current state of devolution in council areas.

1. Surrey

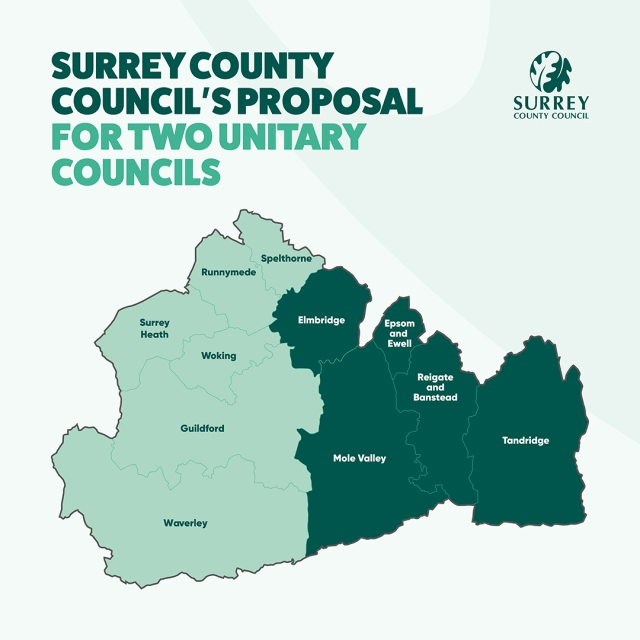

Surrey County Council wants to scrap the current two‑tier system (county + 11 districts/boroughs) and create two new unitary councils: East Surrey and West Surrey. A unitary means one council does everything — bins, roads, social care, planning, the lot.

What’s the issue?

The big fear is money. In the two‑unitary version on the table, West Surrey would include areas with very large debts from past investment plans — notably Woking, Spelthorne and Runnymede.

- A spectacular example of financial mismanagement, Woking effectively went bust in 2023 with £2bn+ of debt (£20k+ per resident). Clearing it will take years.

- Between 2016–2018, Spelthorne council borrowed heavily (using government loans) to buy big commercial properties. Councillors argued this was to replace lost government funding with rental income. By March 2023 the debt stood at about £1.1bn, the second-highest for any district/borough council in England (after Woking).

- Runnymede also has significant borrowing that has attracted government attention.

Put together inside one new West council, those legacy debts and interest costs could soak up a lot of the new council’s budget. That’s why some leaders and residents in places like Guildford and Waverley are nervous: they don’t want to end up paying more to stabilise debts they didn’t rack up.

When councils merge, they have to equalise council tax across the new area. If one side has higher costs (because of debt and interest), there’s pressure to bring everyone up to pay for it. That doesn’t mean bills rocket on day one, there are usually phase‑ins, but the direction of travel for the West looks upwards, unless the government steps in and covers more of the historic debt.

A Government announcement on the next steps of the devolution process is due in the coming weeks.

2. Nottingham

Similar to Surrey, Nottinghamshire is moving toward reorganising councils into two new “unitary” authorities, where one council handles everything.

Nottingham City’s boundary has been a long-running headache. It leaves out nearby urban areas like West Bridgford, Arnold and Beeston – these are areas that feel part of the city, whose residents often use city services, but their council tax naturally goes to their own councils. Since the previous Conservative government’s funding model cut central grants, councils have been pushed to raise more locally through council tax, investments and commercial income. That’s difficult in Nottingham, where about 80% of homes are in bands A and B, so each household brings in less. The result is a smaller tax base and less money to run core services.

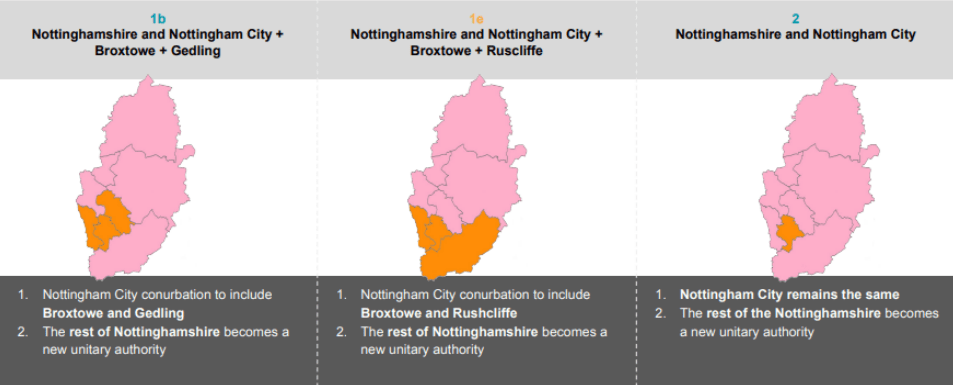

The three options above were proposed earlier this year as potential options to meet the Government’s devolution requirements. A recently published October 2025 report provided an update on proceedings. Following a consultation, residents of Nottingham City were much more likely to be supportive of the reduction to two council areas from nine than residents of the other council areas. However, people that take the time to contribute to a public consultation tend to be those with a negative opinion on the proposal. Overall, option 1e received the greatest support from the public.

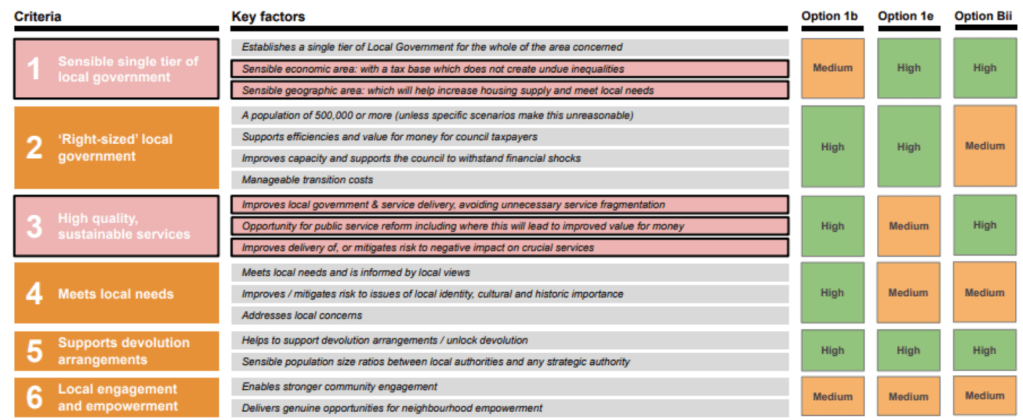

Yet the report recommends that option 1b be used, due to the clearer rural-urban split. Furthermore, an appraisal by PWC (in the report), identifies that this option meets more of the criteria than the other options.

Therefore, Nottingham may need to proceed despite residents’ concerns and prepare for potential backlash. Much of this resistance stems from rural residents valuing their local community identity. However, given the dire state of local authority finances, maintaining the status quo is simply not viable. The Nottinghamshire councils must better communicate the scale of their financial challenges to residents who often have limited understanding of the budgetary pressures they face and why this reorganisation of local government is so desperately needed.

3. Oxfordshire (and Berkshire)

Our final stop is Oxfordshire, an example that breaks the mould by crossing traditional county boundaries.

Oxfordshire has a two-tier system, with a county council and several district councils. However, converting this into a single unitary authority would massively exceed the 500,000 residents that the Government roughly wants per authority. So two of the district councils, Vale of White Horse and South Oxfordshire, decided to look south across the Oxfordshire border into neighbouring Berkshire.

Berkshire is made up of six unitary authorities (Reading Borough, Bracknell Forest, Wokingham, Windsor and Maidenhead, West Berkshire, and Slough), all with populations between 130,000 and 180,000 residents, well short of the 500,000 threshold. South Oxfordshire District Council and Vale of White Horse District Council approached their southerly neighbour, West Berkshire Council, to form a new unitary authority named the “Ridgeway Council” (after the Ridgeway route, an ancient road that runs through all three council areas).

For West Berkshire Council, facing severe financial pressures, this proposal offers a lifeline. As a unitary authority, it’s obliged to provide all services, but with only 160,000 people it’s too small to do so sustainably, especially with out-of-control spending on SEND and social services, an issue plaguing all council areas.

The remaining three Oxfordshire councils (Oxford City, West Oxfordshire, and Cherwell) would form an “Oxford and Shires Council.”

However, this has sparked discontent in communities in the east of West Berkshire (apologies for all the directions), such as Calcot and Tilehurst, which are essentially part of Reading’s urban sprawl. These residents are baffled why they’re being lumped in with Oxfordshire when they’re so economically and socially linked to Reading. Reading Borough Council has requested a boundary change between them and West Berkshire to include these areas.

So here we have a proposed change in Oxfordshire and its knock-on effects, illustrating just how difficult consensus building can be. The formal proposals are to be submitted to the Government at the end of the month with a decision expected sometime next year.

To Conclude

Local government reorganisation is no easy task. The theory makes sense, but in reality there are countless opposing and contrasting voices. Furthermore, can local government even be considered local anymore? Almost all areas not currently under some form of devolution agreement are scrambling to meet the government’s aims. These three examples are just ones I found particularly interesting along the way. Over the coming months, we’ll see more proposals, more protests, and more difficult compromises as councils navigate the impossible task of pleasing everyone while staying solvent.